Photons, Pixels, and Paper

- AsIWandered

- Sep 16, 2019

- 6 min read

The past week has been a blur of information. Arguably, I learned more technical information in those five days than I have in the past three years of teaching myself photography. The implementation of cameras into our phones has distilled the world of photography down to a very basic level. So much of the process has become automated that there is little to no need for any understanding of what's happening inside. As long as the majority of people know "Push here for that Insta-worthy pic!" they'll happily keep firing off selfies. I did much the same with my first few cameras. While there was a learning curve at the very beginning to learn to shoot in the full manual mode of a DSLR camera, I quickly became routine in my approach to taking a photo. The results I was getting seemed good enough and I was never even aware of how much additional knowledge was out there. I made incremental progress, for sure. Every now and then I'd pick up a new skill or bit of knowledge and add it to my tool box of photo techniques. But I never knew what was actually going on in my camera sensor every time I snapped a photo. I threw around the term pixels when trying to determine if I wanted that 20 megapixel camera or 22 megapixel camera, but never fully understood what they did. That is, until this past week.

I won't try to condense 5 pages of notes into one or two paragraphs, but there was a lot of generally useful info that seemed worth sharing for anyone who might be getting into photography, or is already a camera enthusiast and would like to know more. One of the most incredible realizations was just how complex camera systems are. It now comes as quite a feat that engineers have brought them as far as they have and that the technology is as accessible as it is.

Take the camera sensor, for example. When a camera totes its megapixel count, it's referring to the number of individual pixels that make up the entire sensor surface by an order of one million. So on a 20 megapixel sensor, that would be 20 million individual pixels that have been ethced into the sensor. I think the common perception of a pixel is from 90s video games where individual blocks of colors are visible as an image slides around a screen. And that version is correct. But in terms of a pixel that exists in the camera sensor, it is an individual light reader that in turn produces a block of color. Every time a photo is taken, all 20 million pixels take their own individual reading of the photons shooting in from outside the camera. This leads to 20 million voltage readings being recorded as the photons hit a layer of silicon in the sensor and kick out a negative charge. Which leads to 20 million voltage recordings being converted to an exact shade of grey for each particular pixel -- of which, depending on the camera, 65,536 different tones are possible! Which leads to 20 million specific tones being assigned a color value in the form of a red, blue, and green combination by the image processor. Which leads to an image that is a representation of the scene in front of your eye popping up on the LCD screen of your camera. That happens in the span of milliseconds and at the simple push of a button. Every time. NUTS!

Even more nuts was the amount of misinformation that's widespread and that I was guilty of sharing regarding the performance of cameras. Megapixel tends to be the magic word when tantalizing photography enthusiasts over the next hot thing to buy. I myself have been involved with a conversation that goes something along the lines of:

Friend: "Did you see the new camera that just came out? It's 23 megapixels!" Me: "I don't know, it looks good, but this other one has 25 megapixels. I really want to get the best image quality I can."

Friend: "True. Well this other camera is only 1,000 more bucks and gets you 26 megapixels."

It was a mixture of embarrassing and depressing to find out all those pixel-drooling conversations were pretty much useless after learning that pixel count has almost no bearing at all on image quality. The measurements that really matter are: sensor size, pixel size, and bit depth (we'll skip over this, but it refers to the number of grey tones an image can have that was referenced above). Hadn't taken those into account even once in my past camera buying experience. As explained above, pixels are light readers. If you have a physically bigger pixel, it can read more light coming in. Being that images are just recordings of light, a bigger pixel = better image quality. A megapixel count though does not take the pixel size into consideration. It just says how many pixels are available on the sensor. But if a sensor that is 3"x5" that has 20 million pixels is compared to a sensor that is just 1.5"x2.5" with 20 million pixels, some simple math kicks in that says the two sensors are not equal. The pixels on the smaller sensor are tiny compared to that of the larger sensor; there just isn't the same amount of room to fit 20 million pixels. This brings us to the common statement "My phone takes great pictures, it's all I really need for a camera." For many people, this is perfectly true. Phone camera sensors have come along way, they render colors fairly well, and if you only every view them on a screen that has a resolution of 1920x1080 (which is equivalent to just over 2 megapixels) you'll never see a flaw. But think of how much space is allotted in a phone for the camera sensor (it's not much) versus how much is given in a DSLR camera (it's the majority of the camera body). Phone pixels are tiny in comparison, take in no where near as much light, and therefore produce far lower quality images, IF, you were to ever enlarge or print them. As an aspiring photographer, it's always been a little daunting and hard to answer when people ask "Do you think there's still a need for professional photographers when everyone has a good camera in their pocket?" I can finally give a definitive answer that I wrote down in my notes:

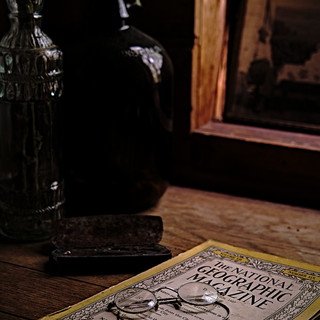

This past week also exposed me to the world of printing paper. Pick any subject, hobby, sport, etc. and you will find a subset of enthusiasts who seriously nerd out over said topic. Printing paper would have been a "topic" if you will that I thought might have fallen outside that rule, but that is incorrect. And I don't mean the broad range of paper types that most people could probably name: a canvas surface; a glossy surface; maybe even a metal surface. There's mattes, there's lustres, there's fine art papers, there's photo papers, there's papers that absorb ink differently, there's papers with different weights and textures, there's different brightness levels, different whiteness levels, there's archival and non archival quality, there's the Moab Entrada Rag Natural 290 and the Moab Entrada Rag Bright 300... the list goes on. In our first printing class, we were shown samples from five different brands. Each brand had about 15 different paper styles with the same image printed on them to show differences in ink absorption and quality. I never thought I would be geeking out over recycled trees but sure enough, I was there with everyone else saying "Oh I love the feel of that! Have you felt this one?? Eh, that one is a little too heavy for me. I REALLY like the texture of this one. Oh, that lustre has just the right amount of shine to it. THIS one. This is me" The slight absurdity of it aside, there really was something special and reactive about touching all the different surfaces and staring into the ink. As our printing teacher explained, tangible products hold attention longer. It is easy to swipe by hundreds of photos on Instagram with having very few, if any, hold a spot in your memory with their impact. But when you can see something up close, touch it with your hands, look into a portrait on paper and feel like the eyes are staring right back at you, that's an effect that's long lasting. In a lot of ways, I think printing can be the real art form of photography. All the other mediums of fine art -- things like sculpture, or painting, or print making, or drawing -- they all produce a tangible product. Digital imagery on the other hand lives almost solely on a screen, until it has the chance to go to print. Then it can become a real piece of art, and the photographer becomes an artist. It makes me excited for the weeks to come when our print labs will begin! And to delve into yet another new area I had no knowledge of.

Here's some photos from the past week; some were taken in class while others were out on my own time. Enjoy!

Comments